What is New Zealand pigmyweed?

New Zealand pigmyweed; Crassula helmsii is listed as an invasive non-native species (INNS) under Schedule 9 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. It is an offence to ‘plant or otherwise cause to grow a plant in the wild’. It is native to Australia and New Zealand and was commercially available from the 1930s as an oxygenating plant for ornamental ponds. It was first recorded in the wild in Essex in 1956 and has since spread through England, Wales and parts of Scotland.

What are INNS?

INNS are species that are not native to a particular area and can have a negative impact on the environment, economy, or human health. INNS can be introduced to an area intentionally (e.g. for agricultural or ornamental purposes) or unintentionally (e.g. as stowaways on vehicles or clothing). Once established, INNS can spread rapidly and outcompete native species for resources, damage ecosystems, and harm human health.

Due to the impact of climate change, native species are likely to face an increased threat as environmental conditions in the UK become more suitable for INNS. This is likely to become a significant threat to biodiversity.

Pigmyweed’s arrival

Pigmyweed was first recorded in the Caledonian Canal, Inverness in 2016 in both terrestrial and aquatic habitats. Ecus was consulted by Scottish Canals to conduct a study to develop innovative assessment and management techniques to control the growth and spread of the plant.

The dangers of pigmyweed

Scottish Canals raised concerns about the potentially significant negative environmental, recreational and economic impacts of pigmyweed on the canal network. The species can out-compete native plants because it has both terrestrial and aquatic forms and a high capacity for regeneration (it readily breaks into small segments and uses dispersal methods of seeds, spores or fruit). It also has little winter die-back and can form dense stands of 100% cover, which has many negative environmental, aesthetic and economic impacts.

Studying the spread of pigmyweed

Ecus’s Scottish ecology team worked with Scottish Canals to carry out a long-term staged study to map the spread of pigmyweed and design treatment methods to manage its growth. The initial mapping study surveyed the full 9.5km stretch of the Eastern District of the Caledonia Canal. The study found the presence of both terrestrial and aquatic forms of pigmyweed and found that the presence strongly correlated with the three marinas on the canal. It was observed that the marinas provided suitable conditions and advantages for the colonisation through water disturbance by boats, and transference on footwear, clothing and dogs.

The study developed high, moderate, low and negligible risk rankings to indicate the likely presence of infestation. The highest category area was likely to be within 10 metres of an active marina with less than 0.5m of water depth on a flat, silted bed with no overhanging vegetation.

Managing the spread of pigmyweed

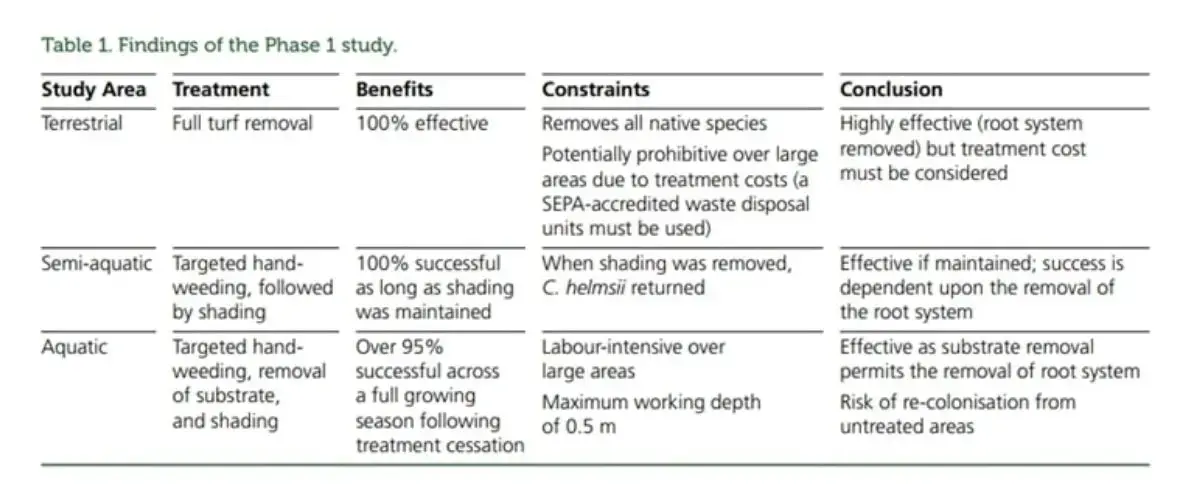

After phase 1 of the study, Ecus’s ecologists were tasked with developing and testing their own innovative solution to treat the presence of pigmyweed. Before this, a successful technique for long-term eradication of the plant hadn’t been found. Ecus was focused on developing an effective, environmentally-friendly treatment that was both scalable and economical to implement, and that incorporated lessons learned from previous studies.

Ecus combined methods of treatment with each approach tailored to the particular area. The approaches combined hand-weeding and aquatic vacuuming with shading using geotextile matting.

- Terrestrial – removal of turf containing pigmyweed combined with 100% shading was the most efficient approach.

- Semi-aquatic – targeted hand-weeding between rocks and 100% shading was used. Targeted hand-weeding permitted the retention of native species.

- Aquatic – hand-weeding was combined with the use of a pond vacuum to remove the growing substrate, followed by long-term 100% shading. All native species were also retained.

Disposal of pigmyweed

Biosecurity was of key importance during this work – after each trip, all clothing, footwear and equipment was cleaned and disinfected thoroughly. All pigmyweed plants were placed in heavy-duty, zip-locked bags and stored in sealed bins before disposal. Disposal methods followed Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) guidelines and involved heating the plants to at least 50oC, then composting for 18 months, and then placing them in a saline solution and heating to 60 oC before final disposal.

Findings

Lessons learned

Ecus successfully mapped the extent and abundance of pigmyweed in the Eastern District of the Caledonian Canal. The identification of risk zones for the colonisation of the plant is key to the long-term management of the species and for planning management strategies for watercourses and waterbodies that contain the species.

The methods used by Ecus during this project yielded positive results in treating the terrestrial and aquatic forms of the plant. A major finding of the study is that the removal of the full root system is key to the success of long-term management.

The long-term management of INNS such as pigmyweed will become a key focus as part of the climate change agenda and the maintenance and management of biodiversity and protection of native species.